Social, Co-located Virtual Reality

Problem Statement: In the Information Interaction Lab, I’m a member of the Co-located, Social VR research group. We analyze the existing landscape of social VR applications and propose design based upon our gathered design gaps. I’ve specifically conducted studies to understand how physical connection among co-located users can impact their joint VR experience and prototyped novel VR hardware designs based upon my findings.

Deliverables: Hardware Prototypes and Environment Setup

My Role: VR Interaction Designer and Researcher

Timeline: 1/2019 to 5/2019

Initial Research

Physical Touch: Foremost, touch is essential and not an ancillary act. Biologically, vagal tone—component of the parasympathetic nervous system that regulates heart rate in response to signals of safety and interest—increases with positive physical touch. An increase in vagal tone decreases heart rate which is associated with increased attentiveness.

Physical contact and touch can be applied in two ways: in a professional setting—surgery, Reiki massage, etc.—or as an expressive, affective act. Even within an expressive context, physical touch is instrumental in shaping an individual’s wellbeing—such as infants’ cognitive development. Physical touch is heavily context dependent; the perception and acceptance of touch is influenced cultural values and the individuals’ relationship.

Brainstorming and Prototyping

Design Inspiration: I’ve been inspired by a variety of sources—from performance art to experimental architecture. Within each domain, I wanted to understand how the design of objects or spaces could influence behavior patterns.

Formed Spaces: Within artificially created environments, designers are able to control all of its elements. Thus, designers can minimize external factors and almost entirely control how individuals feel and interact in the space.

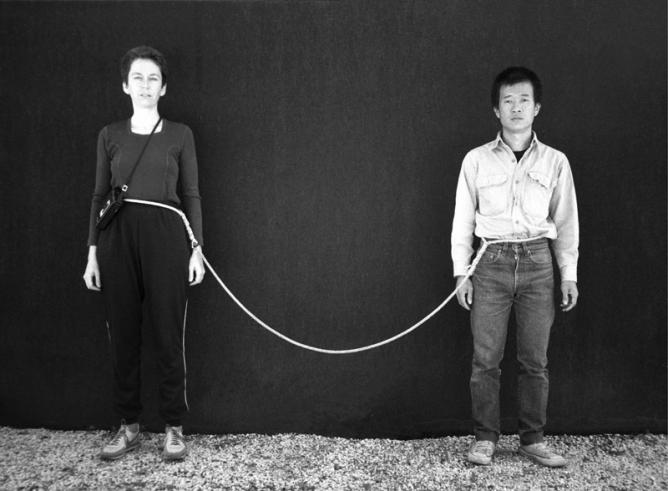

Performance Art: Forcing constraints on existing relationships creates new dimensionality. Similarly, VR hardware can be designed to control human movements and thus completely alter the dynamic between two or more individuals.

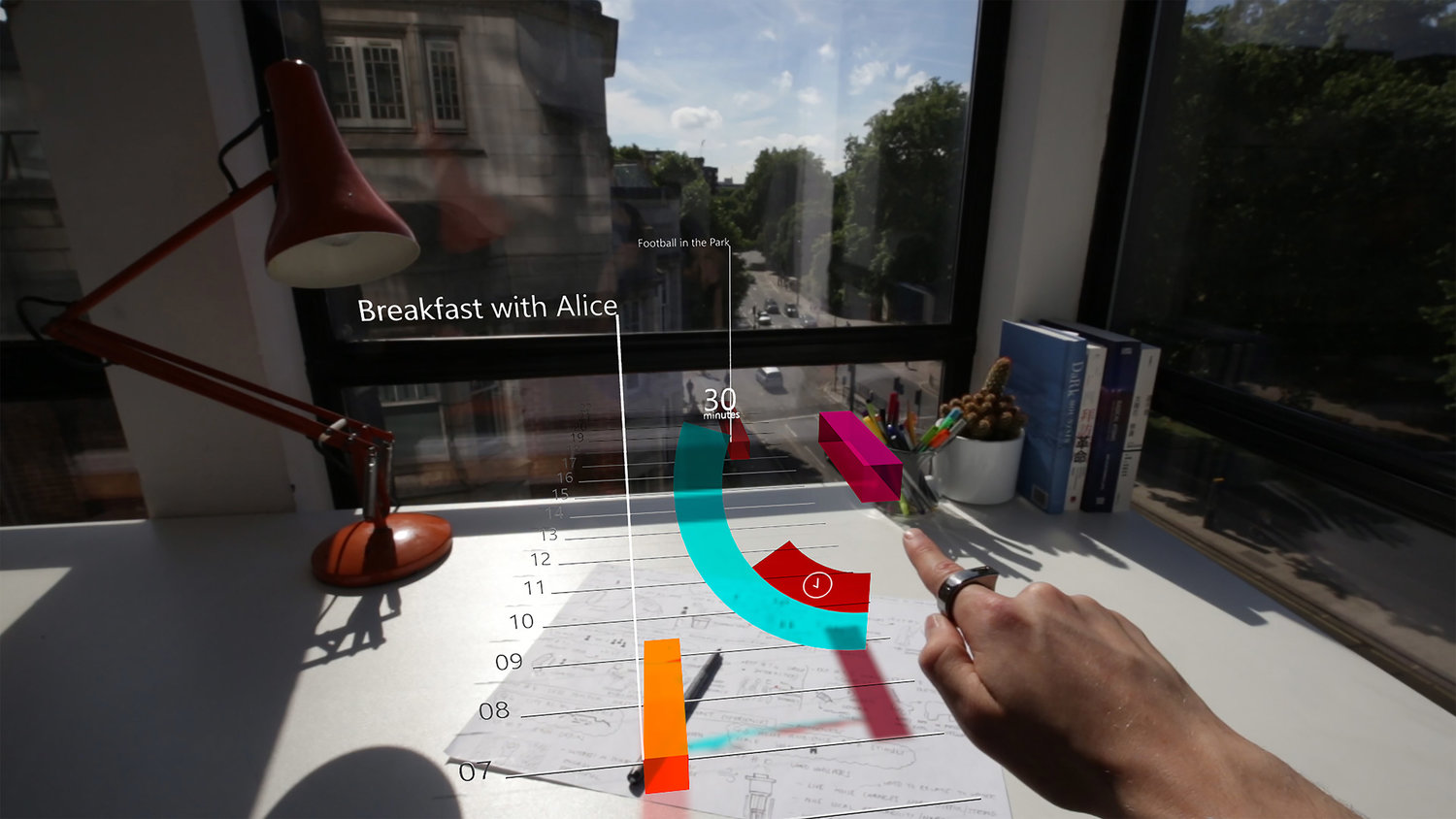

Novel Hardware: Enhancing our physical spaces shouldn’t be limited to what we view within a headset. Rather our virtual visions should be easily accessible and embedded into our existing environment.

Study Concepts: Beyond physical connection, I wanted design full environments to represent the VR content in the physical world. I hypothesized that the environments would bridge the physical/virtual dichotomy and create a more robust experience overall. Also, I wanted to test whether a designed environment would influence the feeling of the physical connectedness between users.

![[Untitled] (29).png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/597e6796a5790a1f46ac8ebc/1557202541869-0PM4RXJ26L9R56DDRQ68/%5BUntitled%5D+%2829%29.png)

![[Untitled] (25).png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/597e6796a5790a1f46ac8ebc/1557176490697-BB4U4OZKMPVOT5LJ10M6/%5BUntitled%5D+%2825%29.png)

Virtual Reality Studies

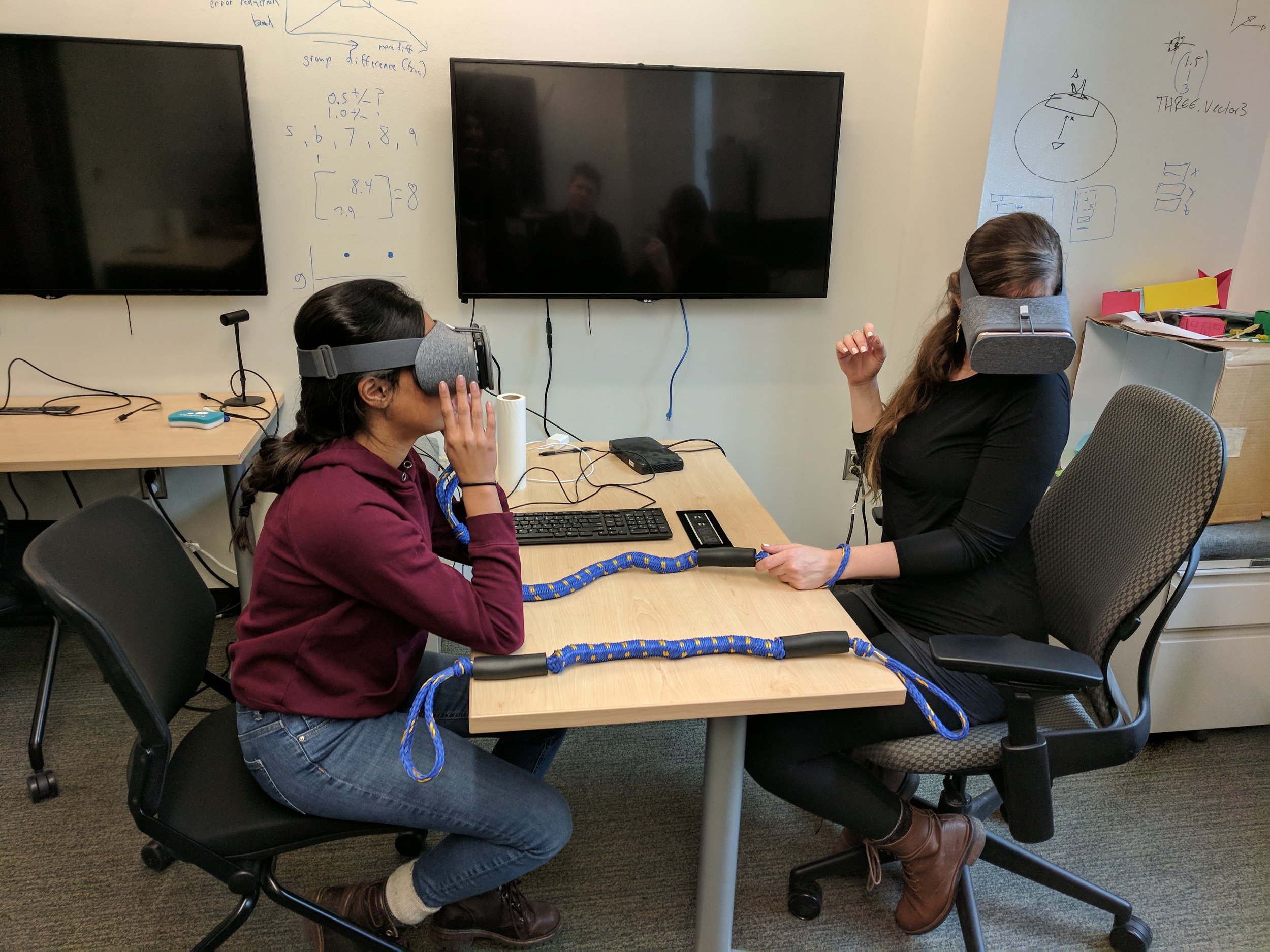

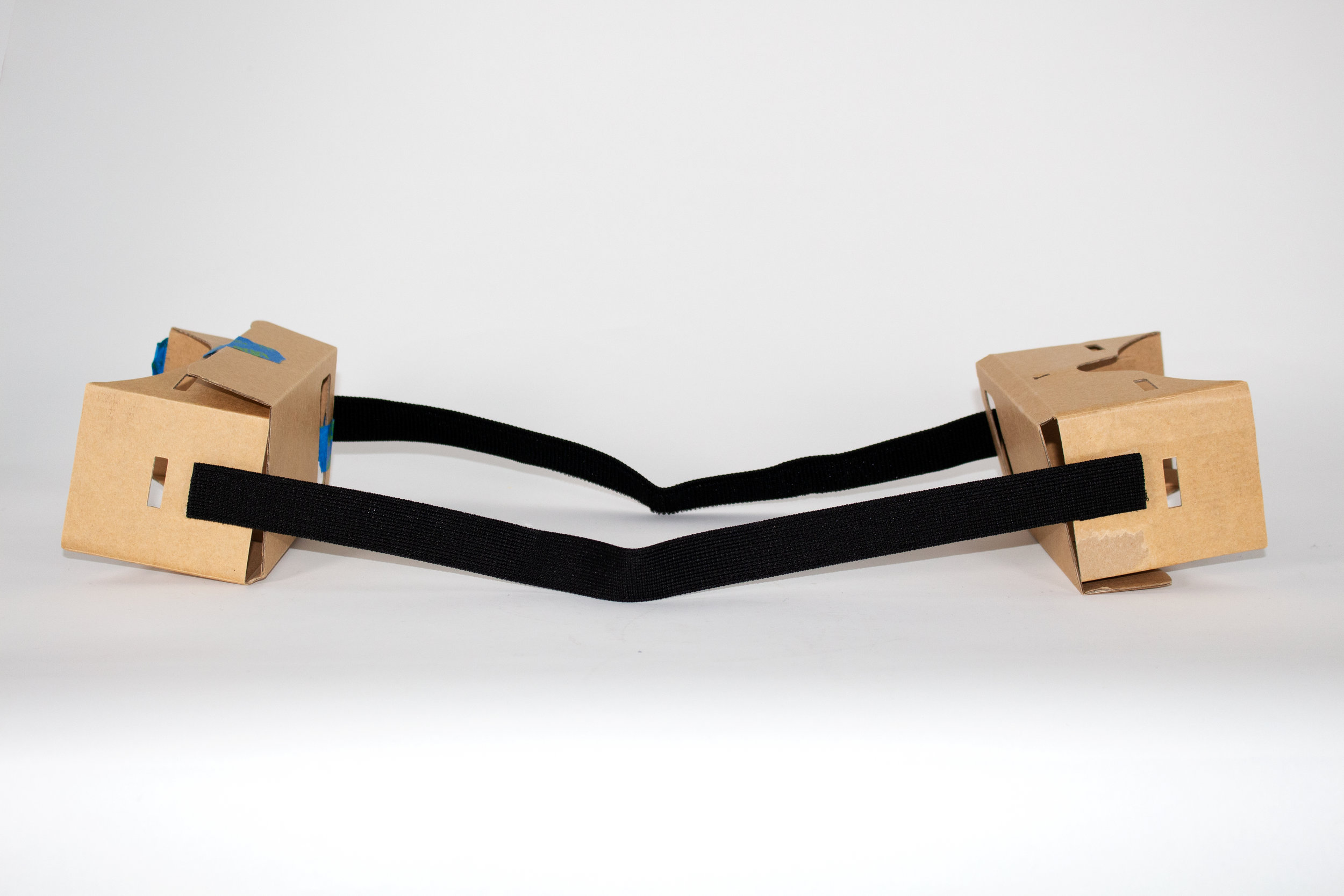

Physical Connection Study: In order to understand how physical connectedness affects people’s existing relationships, I wanted to conduct an experiment with my team members. The experiment entailed two people connected together with rope and experiencing a VR application together. The independent variables were the VR application experiences, the rope flexibility, and the body attachment position.

Study Findings: Being physically anchored made the two VR users feel more aware of the physical world compared to being more fully present in the virtual world. It was noted that the relationship between the two users mattered—they might interact with the rope differently if they were friends, strangers, etc. Additionally, it was important the VR application content contextualized the feeling of being physically connected in virtual reality—for example, being connected at the torso together enhanced the experience of watching a VR rope climbing video.

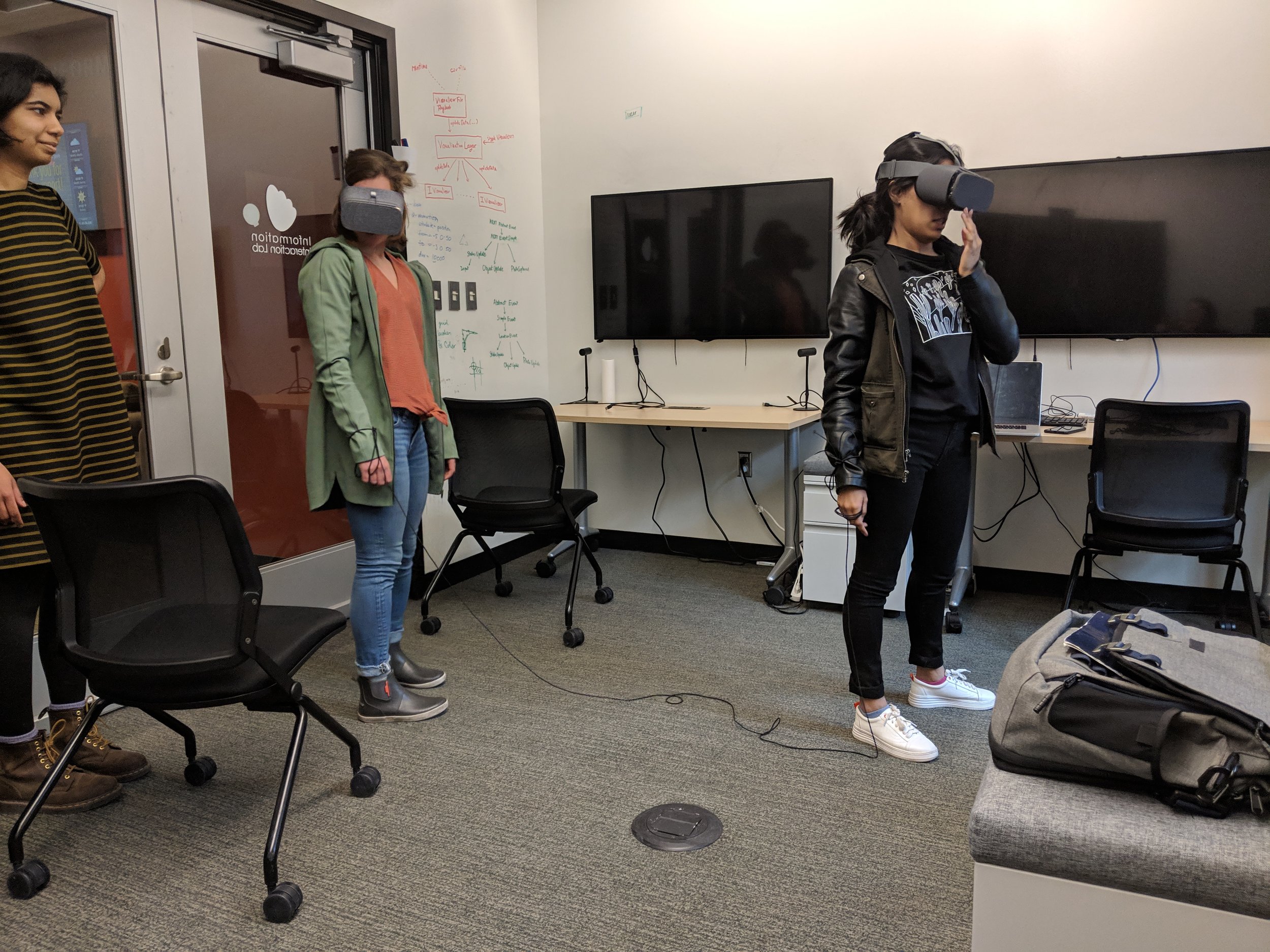

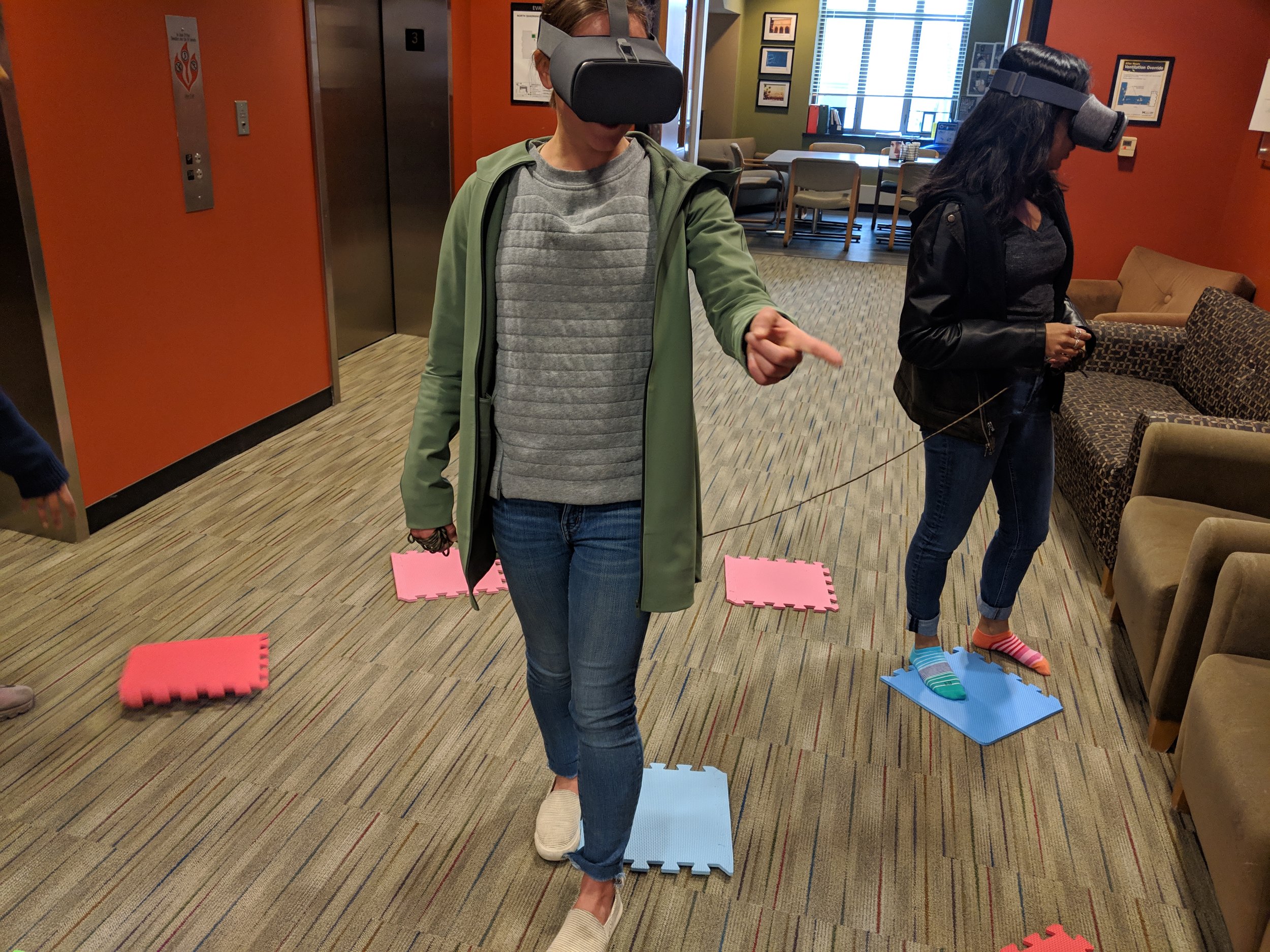

Environments Study: Two VR Environment studies were conducted in which people were physically connected with rope, walking around the designed environment, and experiencing the same VR application together. The independent variables were the environment setup, the VR content, and the connection rope. The first study was set up with rocks on tarp and the VR application was a mountain hiking 360 video. The second study has play mats placed on the ground with a tightrope walking 360 video.

Study Findings: Within the full environment, the rope connection fell short of fully embodying the VR users. It led to a disjointed experience since users could feel each other physically but not interact virtually. Priming the VR environment studies with a set of tasks could create a more intentional experience. Users seemed lost without a common goal to work towards. Calibrating the VR environment components—such as VR application synchronization—would lead to a more cohesive joint VR experience.

Conclusion

User Representation: Subjects stated there was a strong disconnect between physically feeling another co-located VR user and not being able to see them. Solely integrating physical connection widens the physical-virtual dichotomy of VR experiences. Moving forward, it would be best to integrate visual user representation to complement the physical connection between co-located VR users.

Immersion of VR Experience: Subjects often stated that physical contact with other co-located VR users detracted from the VR experience’s immersion; they became more aware of the physical world as opposed to solely existing in the virtual world. However, the decrease in immersion should not necessarily be viewed as a fault but rather a lead for more mixed reality exploration.

Intentional Experiences: In the second study, it became evident that users felt distracted in the VR experience without a set purpose. Certain VR applications lend themselves to ambient experiences. VR applications with specific content—such as tightrope walking—require preliminary context or priming.

Reflection

Poster Presentation: My studies and findings were presented at the UMSI (University of Michigan—School of Information) Exposition. It was exciting to hear the attendees’ personal experiences with VR and their opinions about interacting with co-located users in VR. Questions came up such as how the social interaction would change if more people were in the environment together or whether being physically connected to any object—not necessarily a person—would elicit the same feelings.

Headset Design: Initially, I thought that fabricating novel VR hardware was the best way to engage co-located users through hardware. I maintained a very artifact centered approach and developed conceptual prototypes. However, after conducting studies with physically connected users, it became apparent that it wasn’t the hardware as much the alignment of multiple factors to create the ideal experience. Thus, I moved away an artifact centered approach to designing environments to create intentional VR experiences.

![[Untitled].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/597e6796a5790a1f46ac8ebc/1554485934626-OXA4XVUGATCRFRHQHK76/%5BUntitled%5D.jpg)

![[Untitled] (6).png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/597e6796a5790a1f46ac8ebc/1554485986945-RSXMY21FSO6IRK2UU3JP/%5BUntitled%5D+%286%29.png)

References

“Affecting Touch: Towards a ‘Felt’ Phenomenology of Therapeutic Touch.” Emotional Geographies, by Liz Bondi and Joyce Davidson, Taylor and Francis, 2016.

Chang, Sung Ok. “The Conceptual Structure of Physical Touch in Caring.” Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 33, no. 6, 2001, pp. 820–827., doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01721.x.

Field, Tiffany. “Touch for Socioemotional and Physical Well-Being: A Review.” Developmental Review, vol. 30, no. 4, 2010, pp. 367–383., doi:10.1016/j.dr.2011.01.001.

Kok, Bethany E., et al. “How Positive Emotions Build Physical Health.” Psychological Science, vol. 24, no. 7, 2013, pp. 1123–1132., doi:10.1177/0956797612470827.

Rafaeli, Anat, and Iris Vilnai-Yavetz. “Emotion as a Connection of Physical Artifacts and Organizations.” Organization Science, vol. 15, no. 6, 2004, pp. 671–686., doi:10.1287/orsc.1040.0083.

“Social Connection and Compassion: Important Predictors of Health and Well-Being.” Social Research: An International Quarterly 80 (2):411-430, by Emma Seppala, Timothy Rossomando and James R Doty, 2013.